Participants in punk rock scenes gravitating to country music or roots-bound Americana remains more common than you might suspect, in spite of supposed cultural or political boundaries between often-misunderstood subcultures.

Though the meme-ready Jan. 1978 marquee from Dallas' Longhorn Ballroom that lists the Sex Pistols and Merle Haggard deserves a chuckle, many current acts grounded in the music of both—Jenny Don't and the Spurs, Sarah Shook & the Disarmers, Jackson+Sellers, Croy and the Boys and Girls on Grass, to name five—follow a lineage that at least dates back to the West Coast scenes that offered a creative home to both cowpunk bands and Dwight Yoakam.

Like country, punk means different things to different people. Most interviewees for this story's taste lean traditional, from the honky-tonk music of Ernest Tubb and other rhinestone-studded band leaders to punk's abrasive and often politically-charged alternatives from the 1970s and 1980s to radio-ready pop and hedonistic hard rock.

Discovering Punk and Country

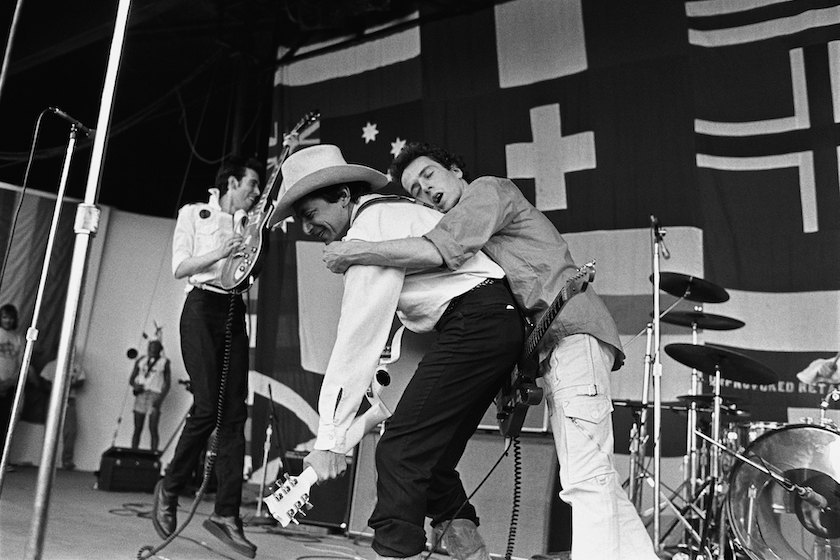

Joe Strummer, guitarist for the British punk rock band The Clash, hangs onto country singer Joe Ely during a performance at a 1979 Monterey, California, concert dubbed "Monterey Pop Festival II." (Photo by George Rose/Getty Images)

Punks turned alt-country and Americana artists that are millennials or older tend to share a similar backstory. Hometown discoveries as teenagers of The Clash (a UK punk band that's fascination with American culture made Texas country outsider Joe Ely an ideal collaborator) and other foundational acts impacted the musical futures of creative types who'd eventually discover that country music isn't so square, after all.

"For me personally, I grew up in rural Oregon," Kelly Halliburton of Portland-based band Jenny Don't and The Spurs told Wide Open Country. "I was a teenage punk rock kid in the '80s, and there's this perception that punk rock and country are sort of natural enemies to one another in a lot of ways. But I've always liked the aesthetic and the early country bands, the '50s and '60s country bands that we are most influenced by in this band. It's hard to explain, but they always had a punk rock attitude about it. It wasn't a very difficult leap to go from listening to punk rock bands to listening to Hank Williams or Pasty Cline or sort of the entry level country music. There's kind of a 'fuck you' attitude [in classic country music] that's what you're looking for as a 16-year-old punk rocker."

Jenny Don't and The Spurs (Shawna Schiro)

Sarah Shook, a singer-songwriter and band leader from North Carolina, didn't take the typical path from punk to country. They developed their taste as an adult because they were homeschooled in a strict, religious environment with zero exposure to non-classical secular music. A former partner turned them on to classic country music first, with punk later puzzle-piecing into their countrified musical vision.

"My introduction to punk was old school punk," Shook said. "It was The Germs and Adolescents and Iggy Pop and all of that type stuff. I immediately identified with it. I love punk music. I love the sound of it and the spirit of it. It was the same kind of feeling as listening to old school country for the first time. I was like, 'I understand this. This is where I fit. I understand this mindset that is against all oppression and against all authority. You are a self-determined person who has a lot of awareness of what's going on in the world and a desire to make things better for everybody.'"

Corey Baum, the namesake of Austin country band Croy and the Boys, discovered punk rock at a young age after receiving a free copy of Epitaph Records' second Punk-O-Rama compilation CD with a pair of Vans. It shaped Baum's appreciation for the sorts of non-pretentious approaches to writing and creating music that set Waylon Jennings, Jessi Colter, Willie Nelson and others apart as outlaws in the 1970s.

"Honky Tonk Heroes was the first real country album that blew my mind and made me fall in love with it all," Baum said. "That was because to me, it had a lot of the rawness of punk music that I liked. A big sticking point for me coming out of punk music is that things that are overproduced are hard for me to enjoy. Aesthetically, so much old country music is raw sounding."

Beyond less-obvious sonic connections between two types of music built on just a few chords and the truth, topical similarities pop up when comparing punk snarl to country sincerity.

"Country music and punk music have a lot of the same motivations, but I feel like punk music is traditionally [about] anger at injustice in the world and anger being a positive thing," Shook explained. "In country music, it's a lot more anger on an individual level, where the person feels like 'I have been wronged by so-and-so while they were out drinking at the bar' or whatnot."

"I had some challenges when I was younger, and I just felt like the lyrical content [of both country and punk] was rooting for the underdog," added Jackson+Sellers' Jade Jackson, a Nashville-based singer-songwriter who works with producer and Social Distortion member Mike Ness. "Punk music was singing for the misfits, and then Hank Williams was so sad and normalizing being a sensitive person. That's how I see them comparing and why I love them both so much."

Parallels between punk's sustained relevance and the origins of country music include a similar sense of communal sufficiency. Punk scenes over time have been localized groups of like-minded people that foster creativity among those more interested in adding their own twist to tradition than chasing current trends— a circumstance not unlike the regional infrastructures that allowed early country and folk radio performers to thrive.

"There's a DIY aspect to country and punk and metal that kind of attracts those people to each other," said Franklin Fatini, host of Cleveland-based radio show Dollar Country. "Back in the day, country is one of the only musics where if all you have is a guitar or all you have is a harmonica... You can technically play roots music with almost nothing, or you can just sing it."

The Roots of Cowpunk

American post-punk band The Gun Club, group portrait, Rome, Italy, 1983. L-R Patricia Morrison, Jeffrey Lee Pierce, Kid Congo Powers, Terry Graham. (Photo by Luciano Viti/Getty Images)

There's multiple potential jumping-off points for understanding country-punk crossovers, from Gram Parson's friendship with Keith Richards to Armadillo World Headquarters in Austin's bridging of the cultural gap between cowboys and hippies. However, the various West Coast scenes since punk broke in America work best when establishing that crossing country and underground rock streams dates back to at least the late 1970s.

"There's a lot of bands from the LA scene that did that from the get-go: combine genres in a really cool and interesting way," explained Barbara Endes of New York bands Girls on Grass and Karen & The Sorrows. "It seems like it was an absolute bonkers time because there's so many people starting bands, and they sounded so different from each other... Just think about the differences between Los Lobos and The Germs and The Go-Gos. It seems like they created a little town within a town and shared all of that stuff."

For instance, crucial Los Angeles punks X brought us country side project The Knitters, featuring Dale Alvin of cowpunk pioneers The Blasters and Jonny Ray Barthel of punk blues band The Red Devils. John Doe, a guitarist and vocalist in both bands, went on to become an Americana tastemaker and the drummer in George Strait's big screen debut, 1992's Pure Country. Other punks to emerge from the West Coast with a clear grasp on roots music include former The Nuns and Rank and File (formerly The Dils) member turned Austin music legend Alejandro Escovedo.

(L-R) John Doe, Sheila E and Alejandro Escovedo perform during the Austin City Limits Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony and Celebration at ACL Live on October 28, 2021 in Austin, Texas. (Photo by Erika Goldring/WireImage)

"I feel like it's a blessing to be one or two generations younger than some of those people like John Doe and Jon Langford [of British post-punks The Mekons and other groups]," Endes added. "The path for this transition has been paved for people our age already. Those people made so many amazing connections and some really amazing music came out of that."

Another California punk band crucial to the punk-to-country pipeline, The Gun Club normalized blending bluesy, gritty rock 'n' roll with pedal steel. Indeed, Jenny Don't credits The Gun Club as a guiding light for the only country-punk band featuring an original member of the Wipers (drummer Sam Henry).

"Most of us have had country music somewhere in the mix somehow for most of our lives," Halliburton added. "Our drummer was sitting in with country bands as a teenager back in the early '70s. So he was simultaneously playing country gigs at honky-tonk bars here in Portland but also an original participant in the first wave of punk rock back when it hit Portland in 1977, '78. There's this coexistence between the two."

Cowpunks—a label that emerged in the 1980s for acts blending punk or new wave with roots influences—becoming commonplace in LA's live music scene created a space to shine for Yoakam, a future Country Music Hall of Famer who at the time was a thousand miles from fitting Nashville's pop-country mold.

''Rank and File initiated that scene about three years ago, and [my band] are on the periphery of it because we have nowhere else to be categorized—and because that scene has accepted us," Yoakam told the Chicago Tribune in 1985. "But we're not a cowpunk band. We're an American country music band. An American honky-tonk hillbilly band.''

Jan. 18, 1986 photo of Dwight Yoakam performing at North Hollywood venue The Palomino. (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Other products of the same state that brought us country music's Bakersfield sound and the country rock that echoed from Laurel Canyon range from clear Johnny Cash fans Social Distortion to Lone Justice, the roots rock outfit that first recorded future Patty Loveless hit "Don't Toss Us Away."

That's not to paint country-inspired punk as nothing more than a true Hollywood story. Bands fitting this narrative popped up all over the map since punk rock's emergence in the 1970s, with The Dead Milkmen masterfully parodying "Tiny Town" mindsets in rural Pennsylvania, the Nirvana-approved Meat Puppets creating its own blend of "desert rock" out of Phoenix and twangy alt-rockers Jason & The Scorchers changing punk perceptions about music made in Nashville. Even CBGB, the New York dive that brought us the Ramones and other East Coast game changers, had a different purpose initially that's tipped off by what its name stood for (Country BlueGrass and Blues) and such surreal booking decisions as Alan Jackson's Feb. 2002 appearance. Still, contemporary punk-turned-country musicians owe a bulk of their creative debt to California's lineage of crate diggers and creative outsiders.

Alan Jackson during performance at CBGB's during Alan Jackson makes rare club appearance at CBGB's in New York City. (Photo by L. Busacca/WireImage)

Despite the musical compatibility that's been present out West for decades now, the most famous instance of strife between blue-collar country fans and city-dwelling punkers took place in California. Country music scholar Amanda Martinez's award-winning academic article "Country Music, Punk and the Struggle over Space in Orange County, 1978-1981" (from the Spring 2021 edition of UCLA's California History) covers the battles (legal and otherwise) that played out between regulars of country bar Zoobies and a punk venue ultimately shut down by city officials, the Cuckoo's Nest. Orange County punk veterans The Vandals covered this as well in Urban Cowboy send-up "Urban Struggle."

"The region's conflicting musical identities came to a head in the city of Costa Mesa, where punk rockers and country music fans violently clashed in a battle over suburban space that revealed a set of competing identities in a region more frequently defined as monolithically conservative, and served as a harbinger for greater political and cultural resistance throughout the Reagan era," Martinez wrote. "In Costa Mesa, joint efforts by country music fans, local police and city leaders to quash the punk rock scene foreshadowed a broader cultural clash within popular music during the 1980s that pitted country music, defined as the sound of Reagan-era conservatism and wholesomeness, against more youthful popular music, which was viewed as corrupting and a target for censorship by conservative groups like the Parents' Music Resource Center (PMRC)."

Resistance to punk in California and elsewhere has waned since the 1980s, in part because the rise of such popular subgenres as emo and pop-punk changed the conversation in the 1990s and beyond.

"As much over the years as I've disparaged these mainstream punk bands like Green Day and bands like that... I've probably talked a lot of shit about that. I think what that did, or even the grunge scene to a certain extent, was introduce middle America to what they interpreted as punk rock and they realized 'okay, this isn't an existential threat to us'," Halliburton said. "That maybe made the country fans a little less hostile than they were 40 years ago to people who looked a little different."

Halliburton admits now that his once-dangerous look as a young punk wasn't that far a cry from the flashy on-stage appearance of someone like Porter Wagoner.

"Me and my friends here in Portland, we were of the big hair and spiky jackets variety of punk rock," he added. "I'll tell you, I have jackets hanging in my closet still that would make Liberace blush. So to go from that to a rhinestone Nudie suit style isn't that much of a leap."

"Do They Owe Us a Living?"

Punk as a concept has as much to do with the D.I.Y. mindset as it does loud, aggressive music. Members of punk scenes book local shows, design merchandise, run independent record labels and fill other roles in a system that seizes the means of production and allows music and art that the mainstream wouldn't touch to exist.

Artists from various genres and walks of life did a very punk thing in 2020 and 2021: they self-recorded projects while stuck at home. In the true spirit of the moment, Croy and the Boys' pandemic covers project flips through punk's back pages. Baum wrote countrified arrangements for DC post-hardcore band Fugazi's "Cashout," far-left Austin legends The Dicks' "Hate the Police" and, strangest of all, UK anarchist collective Crass' "Do They Owe Us a Living?"

"I was listening to that song and felt like, 'Man, this is exactly what I want to say in music right now, the exact message I've been going for'," Baum said. "My joke has kind of been that as my radical politics have gotten more and more pushed to the forefront of my music, that EP is the most radical statement I've made thus far. So I'm kind of hiding behind other peoples' words just to test the waters a little bit. 'Is this too far because I didn't say that. Crass said that.' Then it did really well. 'Okay great, I can continue to push in this direction with my own original material going forward.'"

Baum is far from alone when it comes to blending radical politics and roots music. Perhaps no one involved in country music in 2022 represents all things punk as effectively as Karen Pittelman: Endes' Karen & The Sorrows bandmate, the author of two books about social justice philanthropy and a driving force behind the Gay Ole Opry and Queer Country Quarterly series of concerts.

"She basically puts on mini country festivals with a total punk DIY aesthetic and organization," Endes explained. "Everything she does is inclusive and is just taking care of people and making a cool scene. She helps spread it around Brooklyn and New York, too. She doesn't keep it to herself. She spreads all that goodwill. Karen's like our resident punk godmother who happens to be a country musician."

Read More: All 5 ACM New Female Artist of the Year Hopefuls on a Career-Affirming Nomination

Y'allternative

Musicians Elliott James, Mike Gentile, Cassadee Pope, Jersey Moriarity and Alex Lipshaw of the band Hey Monday visit fuse's "No. 1 Countdown" at fuse Studios on July 9, 2009 in New York City. (Photo by Bryan Bedder/Getty Images)

Punk impacts country beyond decades-old scenes' roles in shaping the fringes of Americana. Influence from the early 2000s popularity of emo, an emotional offshoot of hardcore punk that crossed over into the mainstream, flavors the music of "dirt emo" singer-songwriter Ruston Kelly and Cassadee Pope, the former lead singer of pop-punk band Hey Monday and the coiner of the appropriate subgenre label "y'allternative."

A kindred spirit to Kelly and Pope, Kalie Shorr blurs the thin line between country and emo storytelling with TikTok hit and biting kiss-off "Amy" and other anthems for older millennials.

"There's not many other genres that have people's names and the names of towns in them nearly as much," Shorr said. "A lot of pop is very nondescript and intentionally ambiguous so that everybody can relate. My lyrics are so autobiographical and so detailed. I think I learned how to do that from listening to those two different types of music. Every emo song has someone's name in it, so nobody should be surprised that I have a song called 'Amy.'"

Of course, nothing's quite as emotional as a great country song from any decade, especially as the concerns of aging punks become more introspective.

"It's cool because I do see this progression of people that start out in the punk scene: punk shows, punk bands, touring the punk circuit and all that stuff," Shook said. "Then you get on in years, you settle down and start playing country music. I don't have the answer to that specific phenomenon, but part of me has to wonder if it's because it's tiring caring what's happening in the world all the time. Maybe that's all it is. Maybe it's just like, 'Now I need to focus on myself and all the people that've fucked me over.'"

Sarah Shook and The Disarmers perform at Wildwood Revival's Sundown Social during AMERICANAFEST 2019 on September 15, 2019 in Nashville. (Photo by Erika Goldring/Getty Images)

Check out our punk-to-country pipeline Spotify playlist, which includes songs by acts mentioned above plus bonus tracks by Mojo Nixon, Green on Red, The Beat Farmers, Blood on the Saddle, The Long Ryders, Tex & the Horseheads, Supersuckers, Nine Pound Hammer and Dash Rip Rock.