It's no secret that 1923 — the newest prequel that unpacks the bloody history of the Yellowstone Ranch — is set in one of the darkest decades of our nation's past. With the end of World War I, the controversy of Prohibition and being on the precipice of the Great Depression, life in 1923 was far from easy.

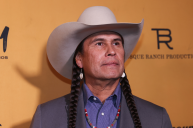

But there's another, less-discussed ugly part of that era: American Indian boarding schools. These government-run schools were designed to assimilate Native American children into mainstream white society by tearing them away from their families and culture. It's a dark story that is brought to life in 1923's first episode by Teonna Rainwater (Aminah Nieves), a presumed descendant of Yellowstone's Thomas Rainwater (Gil Birmingham), who battles the horrifying punishments inflicted by the Irish Catholic nuns and priests trying to rid her of her American Indian identity.

To better understand the horrors depicted in 1923, here are seven facts you need to know about these boarding schools — and where they stand today.

They have been going on for centuries.

Assimilation was nothing new by the time the 20th century rolled around. Religious institutions have been offering "education" to Native Americans since the 1600s via early mission schools after the European colonization of the Americas. Back then, attendance was not mandatory, and parents volunteered to send their children — but that all changed after the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

Carlisle Indian Industrial School opened its doors in 1879 as the first official American Indian boarding school. The model was replicated throughout the United States by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, with hundreds of these boarding schools opening in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Eventually, over 400 were in operation.

Parents were legally forced to send their kids away from home.

After the "success" of the Carlisle school, its creator, Lt. Richard Henry Pratt, requested funding from Congress to build more schools of the same kind. Congress agreed, and by 1902, an estimated 25,000 Native American children were enrolled in these schools, which were government-funded and run by religious organizations. By 1925, there were over 60,000.

Getting an education was required for BIA-registered American Indians. But since removing children from the reservation required parental authorization, many federal officials forced parents to sign off on the paperwork by threatening jail time. In fact, it wasn't until 1978 that Native American parents could legally prevent their children from being taken away. The result was a mass separation of families, with many kids being taken hundreds of miles away from the only home they'd ever known.

Children were stripped of their lives and identities by force.

At the schools, Native American students experienced a complete and utter cultural genocide. Everything associated with them — from their language to their clothing — was taken away from them upon arrival.

Many students were forced to speak English, adopt English names, wear standard-issue uniforms and learn Christian teachings that went against their own spiritual practices. The boys were forced to cut their hair even though long hair was a powerful, sacred symbol of identity in Native American culture. Everything that made these children who they were was systematically banished.

Punishment was extreme.

As depicted in 1923, the punishments for not following these strict rules were brutal. If students were caught speaking their own language or attempting to run away, they were subjected to whippings, beatings and solitary confinement.

Rulers, sticks and belts were used as disciplinary tools — either by their teachers or older students forced into delivering punishment. Runaways were often whipped and, occasionally, punished by running through a gauntlet of students wielding sticks. All of these measures were meant to break the students' spirits and force them into assimilating.

Abuse was rampant.

The schools were known for their physical and emotional mistreatment of children, and serious accounts of abuse have been documented by the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS).

Forced assimilation and violent punishments accounted for much of the physical, mental and emotional abuse that students suffered. The aftermath of this mistreatment resulted in a great deal of trauma and increased risk for substance abuse and mental health issues among survivors. One study found that "former boarding school attendees reported higher rates of current illicit drug use and living with alcohol use disorder, and were significantly more likely to have attempted suicide and experienced suicidal thoughts in their lifetime compared to non-attendees."

Sexual abuse was also common, with many reports of students being raped and molested by teachers, staff members and priests — the adults who were entrusted with protecting and caring for these children. There's no estimate as to how many of these incidents occurred, but experts conclude that "the magnitude of Indian children sexually abused at boarding school must have been great."

Death was a common occurrence.

Many children who attended American Indian boarding schools didn't make it out alive. The buildings were often deteriorating and lacked food, adequate heating, sanitation and medical care. As a result, students would often succumb to diseases such as smallpox, influenza and tuberculosis. And because of the severe emotional trauma and abuse, many committed suicide.

The number of children who died in boarding schools has yet to be fully accounted for due to inadequate or nonexistent records. In fact, many of those who lost their lives during this time remain nameless, buried in unmarked graves at the schools. At least 50 of these burial sites have recently been rediscovered by the Interior Department, leading to at least 500 children so far being uncovered. However, representatives from the department say that "the actual death toll could be in the tens of thousands."

They started shutting down in the late 1920s.

Amid mounting criticism from Native American groups, the U.S. government started to shut down these schools in the late 1920s. A comprehensive investigation was documented in the Meriam Report — a study of Indian conditions since 1850 that was commissioned by the Institute for Government Research — which advocated shutting down the entire system due to its inhumane treatment.

Although some schools were closed, many continued operating. Today, four boarding schools are still in operation by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Education, and the NABS claims that 15 boarding schools receiving federal funding are still open.

The mistreatment and trauma experienced by generations of Native Americans left a lasting impact, one that is only just beginning to be addressed today. The show 1923 serves as a reminder of this dark chapter in history and the need for continued action to help heal those who were affected by it.

People can learn more about the history of Native American boarding schools and the NABS initiatives to help survivors here.

READ MORE: The Newest Generation of 'Yellowstone' Duttons: A '1923' Character Guide