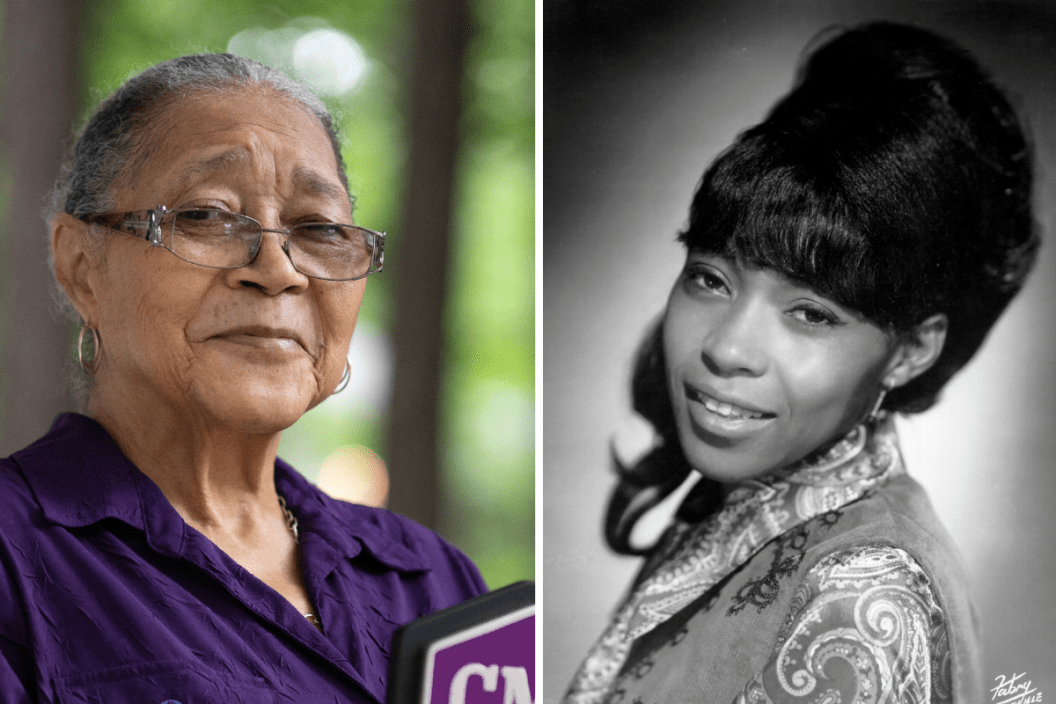

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he legend of Linda Martell rightfully shifted in recent years to the forefront of discussions about country music's often overlooked lineage of Black performers.

Martell (born Thelma Bynem) charted three country singles across 1969 and 1970 for Shelby Singleton's Plantation Records: "Color Him Father," a contemporary hit for songwriter Richard Lewis Spencer's band The Winstons; "Before the Next Teardrop Falls," a future signature song for Freddy Fender; and "Bad Case of the Blues," a yodel-along gem that, along with fiddle and steel-laden deep cut "I Almost Called Your Name," makes Martell's discography a crucial listen for even the pickiest seekers of traditional sounds.

Her lone LP, 1970's Color Me Country, reached No. 40 on Billboard's Top Country Albums chart. Beyond building a stacked back catalog (including at least one post-album 45 issued by Delta Records), Martell became the first Black woman to perform on the Grand Ole Opry stage as a solo artist and guested on Hee Haw.

Martell gets lauded now as a trailblazer thanks to a short yet eventful mainstream run. A body of recorded work that stands the test of time plus vocal support from the likes of Kane Brown, Mickey Guyton, Rissi Palmer and, during a CMA Awards acceptance speech in 2020, Maren Morris culminated in Martell receiving CMT Equal Play honors during the 2021 CMT Music Awards.

Yet as a forthcoming documentary by Martell's granddaughter Marquia Thompson will establish, there's a less uplifting side to this story. Despite early career success, professional mistreatment led to Martell's 1974 retirement from country music— an indictment of the genre's track record when it comes to racial and gender identity equity.

"I wonder now as a 38-year-old woman what my grandmother must have been thinking having tried to pursue her goals and having the issues she had with management and production and that not working out for her," Thompson told Wide Open Country. "I know what it's like to dream and to get that opportunity and in some ways be taken advantage of and exploited."

Sean Rayford/2021 CMT Awards/Getty Images for CMT

Dr. Jada Watson, a professor at the University of Ottawa and principal investigator for SongData, said it's invaluable that Thompson's keeping her film project in the family.

"There are often tendencies within the industry, not just the music industry but entertainment at large, where somebody's story is told not necessarily by that person," Watson explained. "So they can't control the narrative. They can't control how they want to tell the pieces of their story that are hard to tell. So it's about Linda Martell being able to tell it on Linda Martell's terms so she has agency in shaping her story through her experiences and through her eyes. Rather than having somebody from the outside looking in interpreting it, she gets to relay her experience living it."

As importantly, holding the creative reins makes the most fiscal sense for Martell.

"It comes down to it being for her," Thompson said. "The thing is my grandmother never exactly got her due in terms of business in Nashville. That came with a lot of challenges. Knowing how life rights and things like that work within the business, I think it's a bit exploitative to sell her story for everyone else around her to be able to profit off of it and not her."

"[Martell] didn't come out of that career with a lot of money," Watson added. "It's very possible that she made no money from her time in Nashville. Now that her face and her name and her identity and her story is really becoming more well known, she's got a right to the financial side of owning her story."

Besides, a thorough documentary is the most feasible means for 80-year-old Martell to give back to her growing audience.

"She's at an age where she can't go on a tour with all the hype that's surrounding her right now," Thompson said. "There's no way she can stand to benefit from it outside of sharing her story. She's fine, but she's had some health concerns. In that situation, you don't want to overdo it."

Thompson's successful GoFundMe campaign has surpassed its original goal of $20,000: three-fourths of which came from a $10,000 donation from CMT ViacomCBS and, in the case of someone with a global platform truly walking the walk, $5,000 from Morris.

"I've never met her, but talking to some of the folks I know and talking to Rissi about her, Maren is tough like that," Thompson shared when asked about Morris' nationally-televised namedrop of Martell. "I know that probably took a lot of courage for her, especially when Black women aren't exactly celebrated in country music. That brought on a great deal of attention and interest, and it's appreciated for my grandmother to be acknowledged. I remember showing it to her and the way she just smiled. She's always flattered by that type of thing."

Martell eventually left Tennessee for South Carolina, where she became a bus driver and educator. Yet that wasn't the end of the line for her as an onstage performer.

"When I was younger, she traveled all over the Southeast, from Florida up to North Carolina and Virginia, doing R&B covers and stuff like that," Thompson recalled. "She was with a local band called Eazzy. They mostly performed covers. I don't think she ever went out doing anything from her album. It mostly occurred on the weekends. I remember my mom getting ready sometimes and saying, 'I'm going to go see Mama sing tonight.'"

There's overlap between the stories of Martell and Palmer, host of an Apple Music Radio show named after the album Color Me Country. After all, Palmer relocated to the Carolinas and continued making music after being shunned in Music City— despite breaking ground of her own when 2007's "Country Girl" became the first charting country single sung by a Black woman in 20 years.

"I definitely identify with Linda's story," Palmer said. "We both had dreams of stardom and experienced a fleeting moment of success, only to be pushed aside when things didn't go as planned. The biggest difference I see is that I was privileged to have financial and business resources at my disposal and I was born at a time when technology allows artists to work and release music independently. Because of this, I started the Color Me Country Artist Fund, so that lack of money wouldn't keep artists from pursuing their dreams."

Since clearing $20,000, Thompson raised the film's fundraiser goal by $80,000 to cover various expected costs for an in-progress project she hopes to have ready for a 2023 release.

"We pushed it up quite a bit because there's some legal things we anticipate having to deal with regarding her contract," she said. "That and just making sure we get the right coverage and insurance. You know, covering our butts with this film as best we can. And trying to figure out distribution and what that would look like."

It's a hefty sum, yet it's a feasible ask if just a handful of music business movers-and-shakers follow the examples of CMT and Morris.

"I personally would like to see every major label invest in this documentary," Watson said. "It would be an important sign that labels are conscious of the role that the system played in her departure from Nashville. It wasn't just that Shelby Singleton dropped her when Jeannie C. Riley proved to be a bigger hit. It was that he intentionally blocked her from any other opportunities afterwards. That system really needs to be exposed."