For Willi Carlisle, singing is a communal act that can help to free those shackled by suffering. On his 10-song Critterland, the Missouri-based folk singer (he recently moved from Arkansas "to be able to afford a couple of bedrooms on my own") does just that by addressing suicide, addiction, generational responsibility and more.

The follow-up to Carlisle's critically acclaimed predecessor Peculiar, Missouri was recorded with esteemed songwriter Darrell Scott. Best known for songs including "You'll Never Leave Harlan Alive" and "It's A Great Day To Be Alive," Scott welcomed Carlisle into his Tennessee home — "covered in fine art like contemporary paintings and sculptures" — to track the project over three days in early 2023.

Together, the two recorded nearly all the album's parts during that stint, which Carlisle described as the hardest he's ever worked in a studio.

"It's with hesitation that I use a two-dollar word like fecund, but that's what the studio was," Carlisle jokingly tells Wide Open Country. "It's like there was manure all over the place, and we just had to plant the seeds."

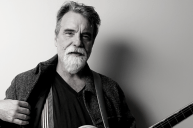

Madison Hurley

The environment proved to be a fruitful one for Carlisle, with it acting as a fertilizer for sonic experimentation that spurred plenty of debate between the luminaries. One such instance came during album closer "The Money Grows On Trees," a seven-minute outlaw epic centering on the marijuana cultivating exploits of Michigander-turned-Arkansan David Mac and Sheriff Ralph Baker, with a spoken-word approach similar to "Peculiar, Missouri" from his previous record.

According to Carlisle, he saw the song with instrumental arrangements, while Scott saw it as a spoken-word piece, leading him to fixate on it to appease his producer. The result is arguably the album's most organic moment, with gentle plucks of the banjo providing an intro and outro to Carlisle's composed rambling as the pattering of rain and thunder further embellish the tale's dark undertones.

"Every night, I'd go into the little cabin I was staying in right next to his house to re-work the instrumental part so he'd like it as much as I did," recalls Carlisle. "Every day, we talked about it and showed each other stuff behind our inspiration before eventually coming to terms on it. It was very process-oriented, which was really cool. I don't think I've worked with anybody that's as good at flipping the switch from writer brain to producer brain and musician brain within a few minutes as well as him."

Another song heavily influenced by Scott — so much so that it almost wasn't included on Critterland — was "Jaybird." The sorrow ballad sees Carlisle reckoning with grief in the aftermath of losing a family member after several suicide attempts. It's a grief and whirlwind of emotions that he admits he's still grappling with, leading to his initial inclination to cut the song.

"With this album I kept looking for little pinholes of light in an otherwise pretty dark record," indicates Carlisle. "At one point, Darrell suggested I just double down, which I thought was interesting. By the time I get in the studio, I've often made peace with what I'm writing about; but in this case I hadn't, which is tough because I feel like there's still a lot of emotions for me to discover in it."

Although Carlisle is still waiting to make his peace with "Jaybird," he reckons that music and the community that comes with it will afford him the grace he seeks. Despite it not going as planned, the "Tulsa's Last Magician" singer also found a community within an intentional one he briefly called home in Stone County, Arkansas. He documents his time there in the title track "Critterland," a bucolic ditty that speaks to the outlaw spirit, the hard work of self-reliance and how alone people are in isolated and impoverished parts of the country.

Willi Carlisle

"Spending time with people who decided to make that an advantage instead of a disadvantage was very empowering," explains Carlisle. "They were people who wanted to be left alone and didn't trust the federal government because they'd been functionally abandoned by them for generations. Me going there was a big dream, and it sucks that it didn't work out. Still, I'm really grateful I got to do it because it left me with the values in the song that I hope to live by."

Throughout Critterland, Carlisle calls upon his personal pain and experiences traversing America in a way that leaves listeners laughing, crying, fuming, reflecting and healing, sometimes all in the same song. It's a craft that few songwriters can match, and a responsibility that Carlisle is more than happy to bear.

"I feel lucky — Critterland came from animals and environs that are so vibrant they couldn't help but tell stories — I feel like I have to share them," confides Carlisle. "I think everyone deserves that kind of vibrancy from the world, but it gets buried sometimes. It's goofy and not without a little irony, but if Critterland is my own joy, despair and fascinations, I hope it leads others to tussle with big questions along with me."