Raichelle Carter didn't have aspirations of becoming a chef, it was something she fell into and discovered she was good at. It was 2009 and Carter, of Harlem, New York was studying psychology at Long Island University. But like most college students she was broke and desperately looking for a way to support herself. So when a friend approached her with an opportunity to make $2,500 working as a cook for the US Open Tennis Championships she couldn't refuse it.

"That's a lot of money when you are in your early twenties," she said, "plus it was easy work." The gig was a cinch, the kitchen would provide a recipe and she would make large batches of appetizers from hummus to spinach dip. "I was thinking if it's money like this in this job and there are more things I can learn, let me see what a career in this looks like."

It took Carter, now 32, six years, but she worked her way up to the coveted executive chef role. She went on to study under well-known chefs such as Shane McBride and those of the Keith McNally organization. Aside from that, she stayed in the kitchen and worked a whopping 120 hours a week. But the grind was necessary to make her dream a reality. Against all odds, she went on to run NYC's The Elk, Georgia's Eastside BBQ and became the first Black woman to co-run and open Brooklyn's Alamo draft house.

Restaurant Industry Racial Inequality

But Carter quickly learned politics and the dark side of the restaurant industry. As a Black woman and a lesbian, she had little in common with the white heterosexual men she worked with, who were also the gatekeepers in the industry. But she didn't let the racial bias and discrimination deter her from climbing New York City's competitive restaurant industry.

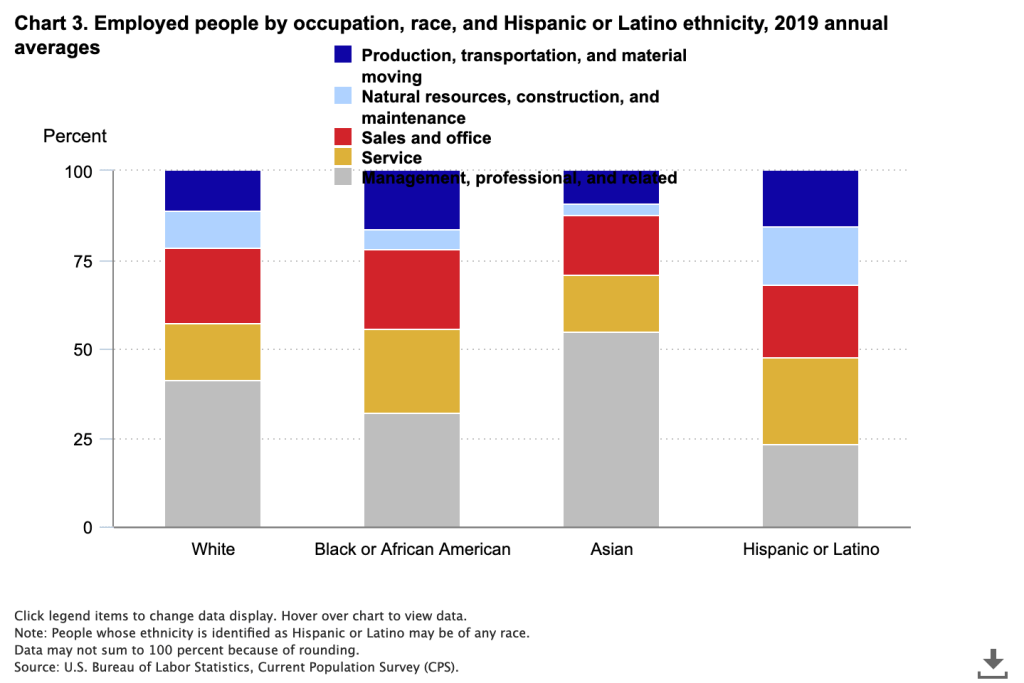

"A person with my talent in the kitchen who is not Black, will get promoted quicker," says Carter. "I see it all the time." Carter has a point; according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Black people make up just 14 percent of Black chefs in the country but when it comes to lower-level positions such as food preparation or dishwashers those numbers rose. "Just being Black in America outside of being a chef is hard. You get overlooked, you get downplayed...all of those things are very real in the culinary world," says Carter.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

After the U.S. open job, Carter went on to work as a line cook at Georgia's Eastside BBQ, a humble eatery on the Lower Eastside of Manhattan. She quickly bonded with Shawn, the top executive who also had shares in the company. Shawn was white, southern and took Carter under his wing. He taught her to cook but how to run a restaurant. She learned to schedule, manage payroll, order for the front and back of the house, and other managerial skills that line cooks typically do not learn. Shawn eventually left the restaurant and moved back to Texas and opened his own restaurant, but he left Carter to become the executive chef. She ran the restaurant for about a year but when Shawn left and the owners became more involved the restaurant's culture changed. Despite her nabbing the position that most cooks dream of she felt it was time to pivot and diversify her portfolio so she went into fine dining and quickly discovered the people she would work for were nothing like Shawn.

Discrimination and Fine Dining

Getty Images

When she moved into the fine-dining space she got a dose of the discrimination in the culinary industry. She had been working at a French restaurant a while, was up for a promotion from line cook to sous chef, and felt like she had it in the bag. But she was slighted when a white coworker who did not have her skills but was a family friend to the owner snagged the role instead. A 2015 study by Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (ROC United), surveyed workers who were denied a promotion, 28% cited race as the primary reason for their lack of advancement. The report also showed that workers of color received 56% lower earnings in comparison to their white coworkers of the same skill set. But Carter didn't let situations like this distract her, she kept her head down and did the work. "When it comes to discrimination, I like to live outside of that realm," says Carter. But she couldn't help but notice a recurring theme. In another restaurant, she was lied to and bullied into taking orders from a line cook who did not have authority over her. She also says that different minority groups within the kitchen would sabotage each other because advancement opportunities were so slim amongst people of color.

A New Beginning

Carter eventually got tired of the kitchen politics, started her own business, and has not looked back. In 2018 she started Grub Kitchen, a Brooklyn-based catering service that also offers weekly meal plans. The company specializes in comfort cuisine and food of the African diaspora, known as a jubilee. She also went on to write a cookbook, Almost a Chef which offers full recipes including her sauces and spices.

When she started her business she sought advice from the man who helped her find her love for cooking, Shawn. She said he taught her that despite the actions of others hard work and determination will always get you to the finish line, "He tells me the industry is full of people pretending to be what they aren't so if you are what you say you are you win the battle every time."

READ: Asheville's First Black-Owned Coffee Shop Brews Coffee and Social Justice