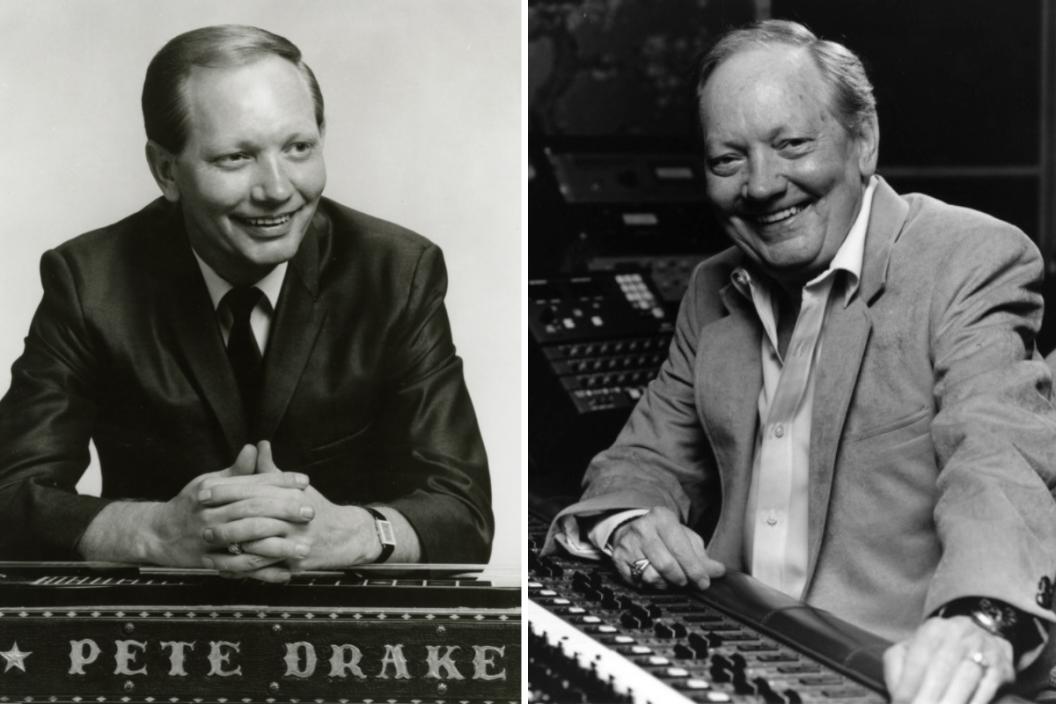

On May 1, 2022, Pete Drake became the first pedal steel guitarist inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. The Georgia native deserves such a high honor, if only for his matchless session work on Tammy Wynette's "Stand By Your Man," Charlie Rich's "Behind Closed Doors," Lynn Anderson's "Rose Garden" and other benchmarks in country music history.

In the bigger picture, Drake worked tirelessly as more than an elite session player, from his 1959 arrival in Nashville to his death in 1988 at the young age of 55.

"A part of the Hall of Fame induction was because Pete contributed so much to country music," said his widow and longtime business partner, Rose Drake, to Wide Open Country. "Not just with his steel playing, but with songwriters and with artists as a producer. He had three different studios, and he contributed a lot to the music industry."

Through his roles as a producer, publishing company owner and record label boss, Drake left a positive impact on younger artists —first as proof that country music wasn't for squares, then as a mentor— before shifting his attention to paying back one of his professional inspirations.

A Rock and Country Innovator

(From left) Pete Drake, Ringo Starr and Jack Drake (photo by Marshall Fallwell Jr. courtesy of Rose Drake)

Drake's synonymous with the "talking steel guitar" sounds he brought to Roger Miller's "Lock, Stock and Teardrops," Jeannie C. Riley's "Mr. Harper" and other noteworthy country songs from the 1960s. Those recordings and Drake's own crossover hit "Forever" helped popularize talk box technology, which per his Hall of Fame bio utilized "a device that directed the steel guitar's sounds into his mouth via a plastic tube, allowing him to turn those sounds into a vocal effect."

Innovation and virtuosity made Drake a sought-after steel guitarist in the '60s and '70s for more than a long succession of country hits and a handful of Elvis Presley film soundtracks. Work on Bob Dylan's Music City trilogy [John Wesley Harding, Nashville Skyline and Self Portrait], Joan Baez's David's Album, Ringo Starr's Beaucoups of Blues and George Harrison's All Things Must Pass made his specialty instrument unironically cool to a young audience that otherwise might've written country off as their parents' music.

"Country music fans back in those days, they were older fans," Rose Drake explained. "Then the new people that started coming to town, a lot of them came because they were introduced to Pete and the steel guitar through these [rock and folk] artists."

Sessions for Harrison's 1970 triple LP All Things Must Pass placed Drake in the same recording studio as rock guitar hero Peter Frampton. Lessons learned from Drake turned 1976's Frampton Comes Alive! into a double live album that, to paraphrase Wayne Campbell, became standard issue in the suburbs.

"Peter Frampton had heard the talker when he was young on a radio commercial," Rose Drake said. "One of the things that Pete and I did was we would record station IDs, sometimes for four or five hours at a time, and send them out to radio stations. Peter had heard one of those, but he didn't know how the sound came about. He didn't know who it was. Then when Pete started playing it in the studio with George Harrison, then he realized that it was Pete. He was so infatuated with it that Pete actually left the talk box there with Peter. Then when Peter started using it a couple of years later, he came up with his own style with it."

Drake also freely shared his talk box secrets with Joe Walsh. The future Eagles guitarist tweaked Drake's process —inspired by the 1940s jazz musician Alvino Rey and enhanced by the work of sound engineer and Heil Talk Box inventor Bob Heil— for the 1973 blues-rock staple "Rocky Mountain Way."

Drake's cross-genre appeal landed him an offer at one point to join Neil Young's touring band. Because Drake didn't want to leave Nashville for long stretches of time and disrupt a constant flow of producer gigs and session work, he suggested longtime Young collaborator Ben Keith for the position.

The Drake School of Music

(From left) Linda Hargrove and Pam Rose with their mentor, Pete Drake (courtesy of Rose Drake)

A before-her-time talent whose greatness transcends her brief creative bond with "Tennessee Whiskey" co-writer Dean Dillon, Linda Hargrove's story captures Drake's passion for helping young dreamers reach their full potential.

"Linda was like the songwriter daughter, he said, that he never had," Rose Drake shared. "I think Linda came to town after she heard the Bob Dylan recordings specifically to look for Pete because she became such a fan of his music. We had a recording studio and we had all of those publishing companies, and so we lived and breathed with new talent all of the time. Pete really enjoyed watching a songwriter develop, and almost all of our songwriters, we'd get them when they first come to Nashville. We didn't sign big-name writers the way the big publishing companies do. We just signed new talent."

The Drake family opened its doors in the 1970s to Pete's understudies, from Hargrove to future steel guitar innovator Paul Franklin.

"They would spend every holiday at our house for the dinners," Rose Drake added. "All summer long, every weekend they'd come to our house and we'd have softball, swimming parties, poker games all night long. They created this atmosphere of writing songs and kind of leaning on each other. Then Pete would put them all in the studio when the studio wasn't booked, and they all learned to be engineers. Linda Hargrove learned to be a producer. She learned to be an engineer. He would take her to recording sessions with him so that she would get to know the producers. Then if anybody needed a rhythm player, he'd say, 'Why don't you give Linda a try?' She became a session musician like that. That's just the way he always operated. He did that with David Allan Coe. He did that with Mary Ann Kennedy and Pam Rose, Jeff Twill, Larry Kingston. He called it the Drake School of Music."

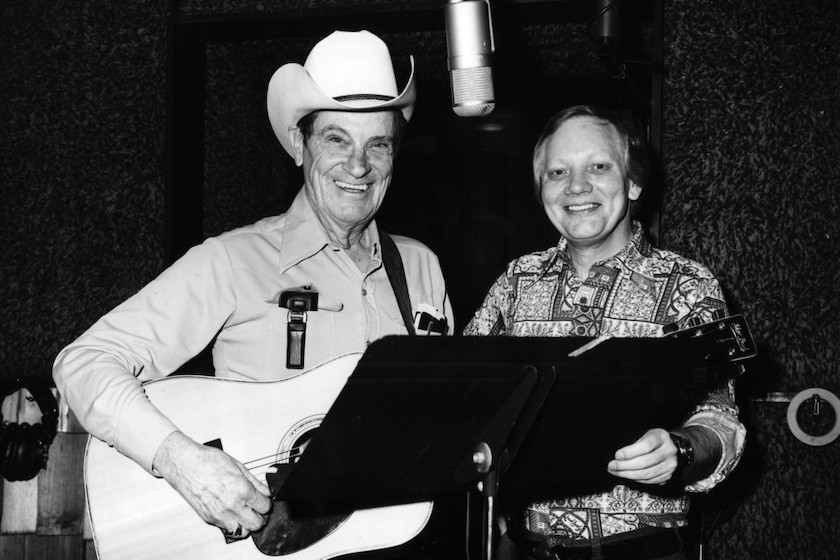

Paying Back Ernest Tubb

Courtesy of Rose Drake

As a record label owner, Drake supported acts shunned by Music Row. For example, his long-running Stop Records imprint released Otis Williams and the Midnight Cowboys, a 1971 album by a Black country artist better known for his work with doo-wop group The Charms.

"Otis and Pete were real close friends, and Pete's bus driver actually introduced them," Rose Drake explained. "They were trying to figure out how to do a new project on Otis Williams because Pete was a fan of his. They figured that since it was Nashville and he already has his whole band that maybe they'd do a country album. Otis just loved the idea of calling it the Midnight Cowboys. At the time, Otis was a barber, I think in Cincinnati. He went back to work, and he didn't go on the road. He wasn't really into promoting it that much."

Drake's crowning achievement as a label head came separate from Stop's deep and rewarding catalog of obscurities and benefitted pop culture icon Ernest Tubb: the longtime boss of Drake's older brother, bassist Jack Drake.

"The very favorite project Pete ever did was Ernest Tubb, The Legend and The Legacy album," Rose Drake said. "Pete's father passed when he was a young boy. Because Jack was with Ernest so much and Pete would come and spend time with him, he felt like Ernest was a second father. He respected him so much."

A 65th birthday present to Tubb, 1979's The Legend and The Legacy featured a who's-who of artists inspired by the formative country singer and band leader, including Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Johnny Paycheck, Charlie Daniels, Conway Twitty, Marty Robbins, Loretta Lynn, Vern Gosdin, George Jones, Merle Haggard, Johnny Cash, Ferlin Hushy and Rich.

"When Ernest was without a record label and MCA had dropped him, Pete tried to get him a record deal and no one wanted Ernest," Rose Drake explained. ""In those days, not a lot of record labels wanted traditional artists. So when it didn't happen, Pete said, 'I've got to find a way to get Ernest some recognition again. We just can't let him be out on the street.' That's when he came up with the idea of bringing the big stars in."

The project launched First Generation Records, which became known in part for its Stars of the Grand Ole Opry series of albums, and honored the work of the Drake family's professional guiding light.

"Ernest Tubb was the kind of man that was a straight shooter," Rose Drake added. "He said what he meant. He was so straightforward that we often would be trying to figure something out and Pete would say, 'Let's step back a minute and think about how would Ernest handle this.' That's the way we ran our business for years."