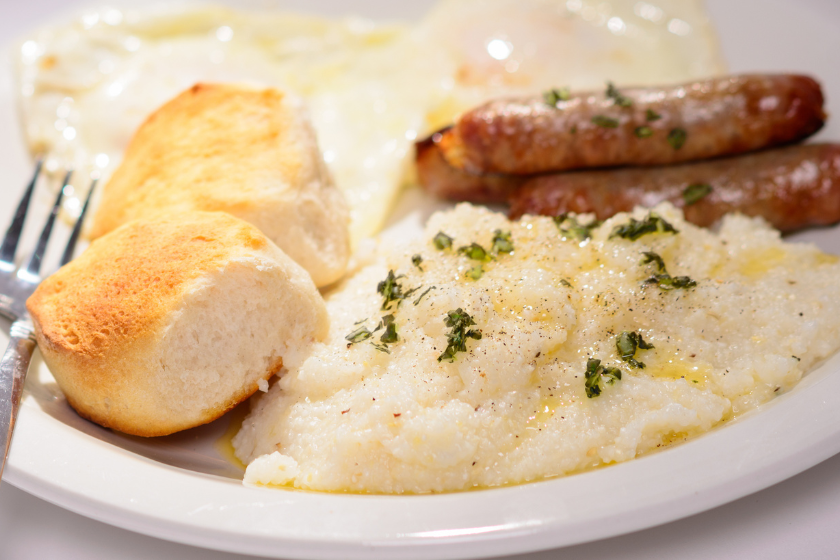

Whether or not you're originally from the South, and whether or not you've tasted them before, you probably have an opinion on grits. Delicious and comforting, or stodgy and congealed? Doctored with salt, sugar, or cheese? Southern grits are a point of both adoration and consternation, a both beloved and hated symbol of the American South. And for good reason: grits have been a staple of the Southern diet for hundreds of years, albeit in various different forms.

Before there was an American South—or an America, for that matter—there were grits. Made from the pulverized kernels of dried, hulled corn, "grits" are typically considered the smaller ground version, while "hominy" references a coarser product. In fact, according to Erin Byers Murray, author of Grits: A Cultural and Culinary Journey Through the South, "Evidence exists that corn was being milled in 8700 B.C. in Central America. There must have been a dish of ground corn and water cooked over heat. It's a food product that's not just historic — it's ancient."

Corn is a food staple native to the Americas. Alongside beans and squash, it was considered one of the "three sisters," a trio of vegetables routinely planted together by Indigenous peoples, as each aided the others' growth. Come the time for summer harvest, the same trio formed the bedrock of pre-Columbian American foodways, often eaten together as a succotash.

However, Indigenous Americans ate corn in myriad preparations, often either drying the kernels for preservation as hominy. When the first European settlers arrived on North American shores—hungry and with barely any agricultural knowledge, as well as no understanding of the new plants and animals that surrounded them—they quickly accepted the seeds and preparation methods offered by their native hosts, including this corn-based porridge.

Today, etymologists believe that the English word "grit" derives from the Old English "grytt," which references European porriages created from oats or wheat. Additionally, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word "hominy" was first recorded by Captain John Smith of the Jamestown exploration. It's believed that it's an Anglicization of the Algonquian word uskatahomen, which means "parched corn."

A Life-Sustaining Vegetable

iStock/Getty Images

As the American South filled with more and more European settlers who pushed natives out of their land and expanded the institution of slavery, corn remained a cheap and deeply sustaining form of sustenance. In fact, for the first three centuries of European settlement, corn had far more everyday uses in the South than all other vegetables combined. By 1849, there were 18 million acres of corn planted across the region, as compared to only 5 million in cotton. Almost a century later, in 1920—the South's highest point for corn planting—there were 46 million acres, representing 44.6 percent of the nation's total crops.

Before the Civil War, Southern grits were often part of a trio of foods given to enslaved folks as part of their rations—the "three Ms," as they were sometimes referred to, consisted of meal, meat, and molasses. As Murray explains in Grits, "the processing of corn was typically performed by a cook who was most often female. That meant that after working a full day, the enslaved would go back to their cabins and still have to dry-grind kernels of corn by hand; or they'd spend an entire day making hominy over an open fire, which would then be eaten whole and reheated, or dried and ground, and then made into a porridge." Grits prepared by enslaved hands would often be present on the long tables of plantation homes as well.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, grits remained a staple food for impoverished Southerners, as they were cheap, accessible, and properly stored would last incredibly long amounts of time. Throughout this history, grits were not only eaten as a porridge, as we think of them now. Rather, grits would be formed into many different dishes, including cornbread and hoecakes.

Modern Grits: What's Old Is New Again

iStock/Getty Images

Although southern grits fell out of favor for much of the twentieth century outside of the impoverished and rural communities that continued to rely on corn for daily sustenance, by the mid-1980s, grits—and other historic Southern staples—had found their way onto tables of nationally renowned restaurants, including Bill Neal's Crook's Corner and Frank Stitt's Highlands Bar and Grill.

With the renewed interest in Southern cuisine in the last ten years—predicated on reestablishing lost foodways such as heirloom ingredients and cooking techniques—grits have once again found themselves at the center of the table. Artisanal producers such as Geechee Boy, Delta Grind, and Anson Mills have expanded the ground-corn offerings available to consumers today while giving us a glimpse—and a taste—of the past. According to the Anson Mills website, "300 years ago, an eight-year-old Native American girl in Charleston would have known more about growing and preparing corn than most of us know today. Our mission at Anson Mills is to return what has been lost. We repatriate flavors of antiquity to promote the wellbeing of all."

So the next time you find yourself about to devour a pile of warm, steaming grits, before you decide how to top those grits—with salt, sugar, or cheese—spend some time considering their trajectory through time onto your table today.

READ: What Are Grits, and How They're Different from Cornmeal and Polenta

This article was originally published October 30, 2017.

Parmesan Grits

Ingredients

- 1 1/2 tsp salt

- 1 cup stone-ground grits

- 1/4 cup finely grated Parmesan

- 3 Tbsp butter

- 2 Tbsp heavy whipping cream

Instructions

- In a saucepan over medium heat, boil 4 cups of water with the salt. Once boiling, whisk in grits and cook, whisking constantly for 1 minute. Return to a boil. Reduce heat to medium-low, and cook until grits are tender, about 20 minutes.

- Whisk in parmesan and butter. Remove from heat and stir in heavy cream. Top with a pat of butter if desired.