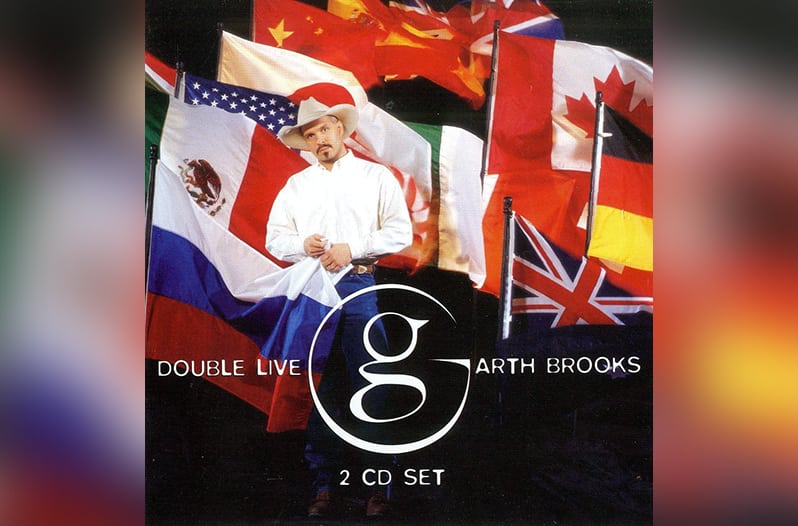

Last week, Garth Brooks finally shared his highly anticipated new live album, Triple Live. Well, sorta. It was announced that fans who tuned into Brooks' Inside Studio G on Facebook Live would be given the chance to download a free preview of the surefire hit album. It's safe to assume that Triple Live, like its' predecessors, Double Live and the slightly different Double Live: 25th Anniversary Edition, will be released sometime this November.

It will be 20 years come this November that Brooks released the 26-track double-album. Like many young kids in Texas (and, well the U.S. in general) my parents found that Double Live was a perfect stocking stuffer for Christmas, which was rolling right around the corner. It was conveniently placed at every Wal-Mart across the nation and was a bargain at only $13.99. (If I remember correctly, they paired it with Sevens, which Brooks released the year before).

I'd just turned 11 and like many 11-year-olds, my taste in music was almost exclusively based on what was playing in the cab my parents' pick-up trucks and kitchen radios. They were Garth Brooks fans. That, in turn, made me a Garth Brooks fan. When I returned to school after the holiday break, I'd say the vast majority of my classmates had also received Double Live in their Christmas haul.

For a kid, what made Double Live special was the fact that it played out like a greatest hits album. Though I've grown to love the deep cuts of the under-appreciated Brooks songbook, Double Live was essentially every song you'd heard on the radio. "Papa Loved Mama," "Standing Outside The Fire," "American Honky-Tonk Bar Association," "Ain't Goin' Down ('Til The Sun Comes Up," "Rodeo" and so on for seemingly forever—you name it, it was there.

Disc openers "Callin' Baton Rouge" and "Ain't Goin' Down ('Til The Sun Comes Up) start off with low rumbles of a crowd noise and a lone instrument (a sawing fiddle on "Callin' Baton Rouge" and a cajun harmonica on "Ain't Goin' Down") before Brooks and the band bust down the doors to join the party. It was guitar smashing and sweat-soaked pastel brushpoppers. You can't help but become enthralled by Brooks presence.

There's a fiery electric buzz on songs such as modern murder ballad "Papa Loved Mama," the anthemic "Standing Outside The Fire," and dusty cowboy stompers "Rodeo" and "Much Too Young (To Feel This Damn Old)." You sing along as if you know one damn thing about feeling too old.

There's an undeniable charm with Brooks. He's a showman. He's maybe the showman of all showmen. It rivals theater and the spotlight is, for the most part, solely on him. It's obviously packed with party starters. When "Longneck Bottle" or "Two of a Kind, Workin' On a Full House" kicks off, everyone joins in for an impromptu honky-tonk choir. Everyone.

And that's what makes Brooks' sense of time and situation so special. It's those barn burners booking intimate ballads like "The Beaches of Cheyenne," "If Tomorrow Never Comes," and the unrivaled beauty of Bob Dylan's "To Make You Feel My Love." He somehow makes these feel like small moments despite being in front of thousands of people. He closes his eyes and we all disappear.

Looking back, it's pure nostalgia. You can't help but realize now that Brooks' first live album was mainly a product for mass consumption rather than an artistic statement. In some respects, it's a sterile look at a Brooks' live show.

Anyone who has attended a Brooks concert knows there isn't a single second in which Brooks isn't awestruck and whole-heartedly appreciative. It's a natural high that launches him into running around to every square inch of the stage. For those brief hours, he's the king of the world. That magic doesn't translate over into Double Live just quite like it should.

That's mainly due to the lack of interaction between Brooks and the crowd. But when it does happen, it's a golden hour. It's primarily captured on "The Thunder Rolls" and "Friends in Low Places" and mainly due to them being mythic extended cuts—often dubbed "the long versions."

Brooks sings "3:30 in the morning, not a soul in sight" and well, it becomes 3:30 in the morning. He lets it roll on until the final verse and in an instant, it becomes a vengeful murder ballad that has everyone eating out of Brooks' hand. Likewise, "Friends in Low Places" extends out further than you previously remembered. He takes out to The Oasis for a round of whiskey shots and pitchers of beer.

"You're exactly right. What would a Garth live album be without the live version of 'Friends in Low Places'? Because it's only here where you can find that mysterious third verse that goes on the end of the little song," says Brooks mid-song.

Every so often, we get a Brooks freakout—"NOW IT'S ALL YOU GUYS" on "Friends in Low Places," the way he screams Louisiana on "Callin' Baton Rouge," "we call them WEEEEEEAK" on "Standing Outside the Fire" and so on. There's nuance in his delivery on "That Summer," Billy Joel's "Shameless," "Unanswered Prayer" and "The River" that give an added punch of fiery passion unseen in their studio album counterparts.

Of course, Double Live closer "The Dance" is special as well. It's one of the rawest and uncalculated moments on the release. It's a singalong lullaby that truly feels like the closing credits of your favorite movie. That dark and lonesome piano cues your signal to swell up.

READ MORE: The Story Behind Garth Brooks' Iconic Hit, "The Dance"

If they'd have somehow bottled up those specific moments, Double Live would have been unquestionably special. Granted, that's easier said than done. When Brooks is unscripted and off the cuff, that's when he's his best. When he's engaged with an audience, that's when he shines.

Still, you take the lumps with Double Live. There's a reason it's sold over 6 million copies worldwide. You're listening not because it's a double shot of Brooks live. Rather, you're listening because it's Brooks. That's special enough.